Pennsylvania church accused of using ‘mob boss approach’ to pressure

lawmakers who support bill giving victims of abuse more time to sue

abusers

The lobbying campaign against the legislation is being led by Philadelphia archbishop Charles Chaput, a staunch conservative who recently created a stir after inadvertently sending an email to a state representative Jamie Santora, in which he accused the lawmaker of “betraying” the church and said Santora would suffer “consequences” for his support of the legislation. The email was also sent to a senior staff member in Chaput’s office, who was apparently the only intended recipient.

The email has infuriated some Catholic lawmakers, who say they voted their conscience in support of the legislation on behalf of sexual abuse victims. One Republican legislator, Mike Vereb, accused the archbishop of using mafia-style tactics.

“This mob boss approach of having legislators called out, he really went right up to the line,” Vereb told the Guardian. “He is going down a road that is frankly dangerous for the status of the church in terms of it being a non-profit.”

Under US tax laws, organisations like churches that are classified as non-profit groups are not supposed to be engaged in political activity, though they are allowed to publish legislators’ voting records in some cases.

At stake in the contentious fight is a state bill that would allow victims of sexual abuse to file civil claims against their abusers, and those who knew of abuse, until they are 50 years old. Under current law, victims can only file suit until they are 30 years old. The proposal overwhelmingly passed the state lower house in a bipartisan vote in April but appears to have stalled in the state senate, where some believe it might not pass.

If it does pass and is signed by the governor, the legislation could cost the Catholic church tens of millions of dollars following a spate of abuse allegations in the state, including a devastating report released earlier this year by a grand jury that detailed how two Catholic bishops in the Altoona-Johnstown diocese covered up the abuse of hundreds of children by more than 50 priests over a 40-year period.

But it is the church’s personal targeting of legislators, rather than the legislation itself, that is drawing the most scrutiny, particularly among a small group of lawmakers who are both Republican and Catholic – and say they have steadfastly supported the church’s positions on other issues such as abortion and private Catholic schools.

One Catholic state representative named Martina White went on a local talk radio programme to describe how she had been “crushed” when she was disinvited to several planned events at local Catholic parishes because of her support for the bill.

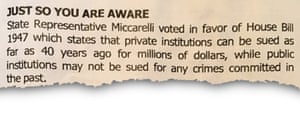

Another representative, Nick Miccarelli, said he was baffled and upset when he learned that his support for the proposed legislation was included in his church’s bulletin under the heading “Just So You are Aware”, including information that he said was blatantly misleading about the nature of the bill.

“I’ve never had anything but good things to say [about my parish], so it was a heck of a shot, when you are out there telling people how much you think of a place, and that place doesn’t even give you a phone call before they print ... something that was not an accurate statement,” he said. Miccarelli was angered by the bulletin’s suggestion that the lawmakers had sought to protect public institutions while targeting private ones like churches.

Representative Thomas Murt, who attends mass daily, told a colleague he was “devastated” when the priest at his church spoke about Murt’s support of the legislation, even as Murt was sitting in the pews. The priest’s discussion of the legislation went on for 40 minutes.

“Tom was really upset that no where did the priest mention the kids. Anyone who knows Tom knows he is extremely sincere on this issue. He just wants to do what is right,” the colleague said, asking not to be named.

Gavin said the Philadelphia archbishop had sent a letter explaining the church’s opposition to the bill to 219 parishes throughout the area, which had been read or made available during Mass.

“I am not aware of any situations involving a pastor lambasting an elected official and they weren’t directed to do so. I do know of many instances where pastors shared with parishioners how representatives voted on [the bill]. They shared knowledge that is already public,” Gavin said.

Chaput’s criticism of the bill is centred on claims that the Philadelphia archdiocese already has a “genuine and longstanding commitment” to abuse victims; that it is committed to protecting children now; and that the new law would only apply to churches and private institutions, but still make public institutions like schools and prisons immune from similar retroactive civil suits in abuse cases.

But the Catholic lawmakers who support the bill reject that claim as a red herring, because public institutions like schools receive some immunity from lawsuits in order to protect taxpayers. All said they had been deeply moved by the testimony of fellow legislator Mark Rozzi, who was raped by a priest when he was 13 years old and said the bill would offer victims some justice after years of being “stonewalled”.

“He is the most vehement supporter of the secrecy of the Catholic church over pedophiles. He fights any authority over his own, even when it is a matter of criminal law,” Fitz-Gerald said.

One expert, Marci Hamilton, the chair of public law at Cardoza School of Law, said similar legislation that has passed in four other states, including California, has only been used by a relatively small number of victims.

“This is a way for the whole culture to say to survivors that they matter and that they are believed. Because when a survivor comes forward, in most states they are beyond the statute of limitations [to bring civil claims] and the message they get from the law is that what happened to you doesn’t matter,” she said.

Hamilton claimed that Chaput had been brought to Pennsylvania after helping to kill similar legislation in Colorado.

“It is clear they [the church] have bought into this strategy, which is to turn the church into the victim and to portray the victims as just seeking money and triangulating the parishioners against the victims, by saying the parish will go bankrupt and have to close schools,” Hamilton said.

Jamie Santora, the Republican legislator who several people said received the email from Chaput, declined to comment on the email specifically. But he acknowledged he had been accused by a high-ranking church official of betraying his church.

“I don’t feel I did betray my church. Growing up Catholic gave me the ability to vote the way I did. To me that was the morally correct vote, by choosing victims over abusers,” he said.

Asked to comment, the spokesman for the Philadelphia archbishop said: “Elected officials are accountable to the people who elected them. There’s nothing odd in that. It’s how the system works.”