Volunteers need help: car boots and spare space to save history going back to the 1950s

Australian retro computer fans, it's time to mobilise: the shoestring volunteers trying to preserve computer history here are the end of their lease, money, and wits.

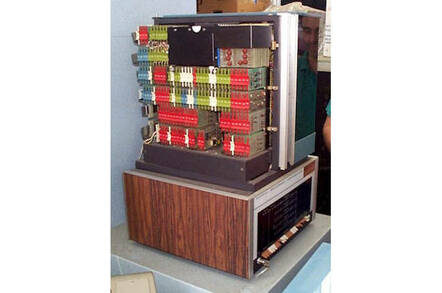

So if you have storage space and a sentimental feeling about, say, a DEC MicroVAX 4000, part of a PDP-11, or a Control Data CDC-6600 backplane, you'll be welcomed with open arms by the Australian Computer History Museum.

Things are so dire that the group's treasurer John Geremin told Vulture South the first priority to save the collection from the planned demolition of its warehouse space is people (probably Sydneysiders) willing to take car-boots full of the “small stuff” temporarily, to provide access to PDP-11-size machines on wheels.

There's rather a lot of stuff – the museum's catalogue, is here, and you can see the organisation is struggling even to organise the inventory.

The ambitious attempt to save machines from the tip – the group claims a collection dating back to the 1950s – was always a volunteer effort, and hasn't ever reached the point of creating an exhibition space.

Calling for help, historian Dr Peter Hobbins wrote that the repository of computers, peripherals, media and documentation spans the 1950s to the 2000s, and is being held “in a 200 square metre warehouse at 888 Woodville Road, Villawood, which will be demolished in two weeks.”

Are these the last weeks for the Australian Computer Museum? Their last refuge, a storage facility in Villawood, will be demolished in a fortnight and the members are urgently seeking a new home for the collection, or even just for anything you want to rescue as a 'custodian' pic.twitter.com/94efZy4W1H

— Peter Hobbins (@history2wheeler) July 28, 2018 That countdown has already lost a couple of days, since Hobbins' post was on July 30.

At this point, even temporary homes would do: “the volunteers - mostly former programmers and engineers in their 70s - are at the desperate point of suggesting that anybody who wants anything from their collection can just come along and take it” (noting that if it secures a replacement space, the museum would want its property returned).

Geremin told Vulture South the collection owes its existence to the vision of a former Digital Equipment Corporation Australian boss, Max Burnet. While in that role, Geremin said, Burnet started a historical collection by offering companies discounts if, instead of junking their PDP-series machines when their shiny new VAX boxen arrived, they sent them back to DEC for the collection.

(Old-timers of the Sydney tech scene will probably remember the historical Digital kit displayed in the large foyer of its Lane Cove offices – El Reg.)

Like-minded collaborators from around the industry became involved over time, but with only volunteers and limited funds, they've only been able to make and catalogue the collection. Geremin said if the collection can be saved, they hope to garner resources to get some of the machines restored, functioning, and on display somewhere.

That would need resources – once the present crisis is dealt with.

However, Geremin said, it's been hard to attract interest here (the Computer History Museum in America has shown more interest, but it's too distant to make a practical difference).

“There doesn't seem to be any acknowledgement of engineering history in Australia,” he told Vulture South.

“Australia has made enormous contributions to advances in technology,” Geremin said. “Through WW2, Australia was a major exporter of electromechanical computer technology of the day. The biggest installation I was aware of had 132 functioning terminals.”

Everybody knows about the CSIRO's CSIRAC, the first electronic computer to play music and now preserved at Melbourne Museum, but Geremin said there's much more to preserve. Even imported machines made an important contribution to the country, he said.

Source