1. Introduction

In the course of the

SARS-CoV2 pandemic, new regulatory frameworks were put in place that

allowed for the expedited review of data and admission of new vaccines

without safety data [1].

Many of the new vaccines use completely new technologies that have

never been used in humans before. The rationale for this action was that

the pandemic was such a ubiquitous and dangerous threat that it

warrants exceptional measures. In due course, the vaccination campaign

against SARS-CoV2 has started. To date (18 June 2021), roughly 304.5

million vaccination doses have been administered in the EU (https://qap.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#distribution-tab

(accessed on 18 June 2021)), mostly the vector vaccination product

developed by the Oxford vaccination group and marketed by AstraZeneca,

Vaxzevria [2] (approximately 25% coverage in the EU), the RNA vaccination product of BioNTec marketed by Pfizer, Comirnaty [3,4] (approximately 60%), and the mRNA vaccination product developed by Moderna [5]

(approximately 10%). Others account for only around 5% of all

vaccinations. As these vaccines have never been tested for their safety

in prospective post-marketing surveillance studies, we thought it useful

to determine the effectiveness of the vaccines and to compare them with

the costs in terms of side effects.

2. Methods

We used a large Israeli field study [6]

that involved approximately one million persons and the data reported

therein to calculate the number needed to vaccinate (NNTV) to prevent

one case of SARS-CoV2 infection and to prevent one death caused by

COVID-19. In addition, we used the most prominent trial data from

regulatory phase 3 trials to assess the NNTV [4,5,7].

The NNTV is the reciprocal of the absolute risk difference between risk

in the treated group and in the control group, expressed as decimals.

To give an artificial example: An absolute risk difference between a

risk of 0.8 in the control group and a risk of 0.3 in the treated group

would result in an absolute risk difference of 0.5; thus, the number

needed to treat or the NNTV would be 1/0.5 = 2. This is the clinical

effectiveness of the vaccine.

We checked the Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) database of the European Medicine Agency (EMA: http://www.adrreports.eu/en/search_subst.html#,

accessed on 28 May 2021; the COVID-19 vaccines are accessible under “C”

in the index). Looking up the number of single cases with side effects

reported for the three most widely used vaccines (Comirnaty by

BioNTech/Pfizer, the vector vaccination product Vaxzevria marketed by

AstraZeneca, and the mRNA vaccine by Moderna) by country, we discovered

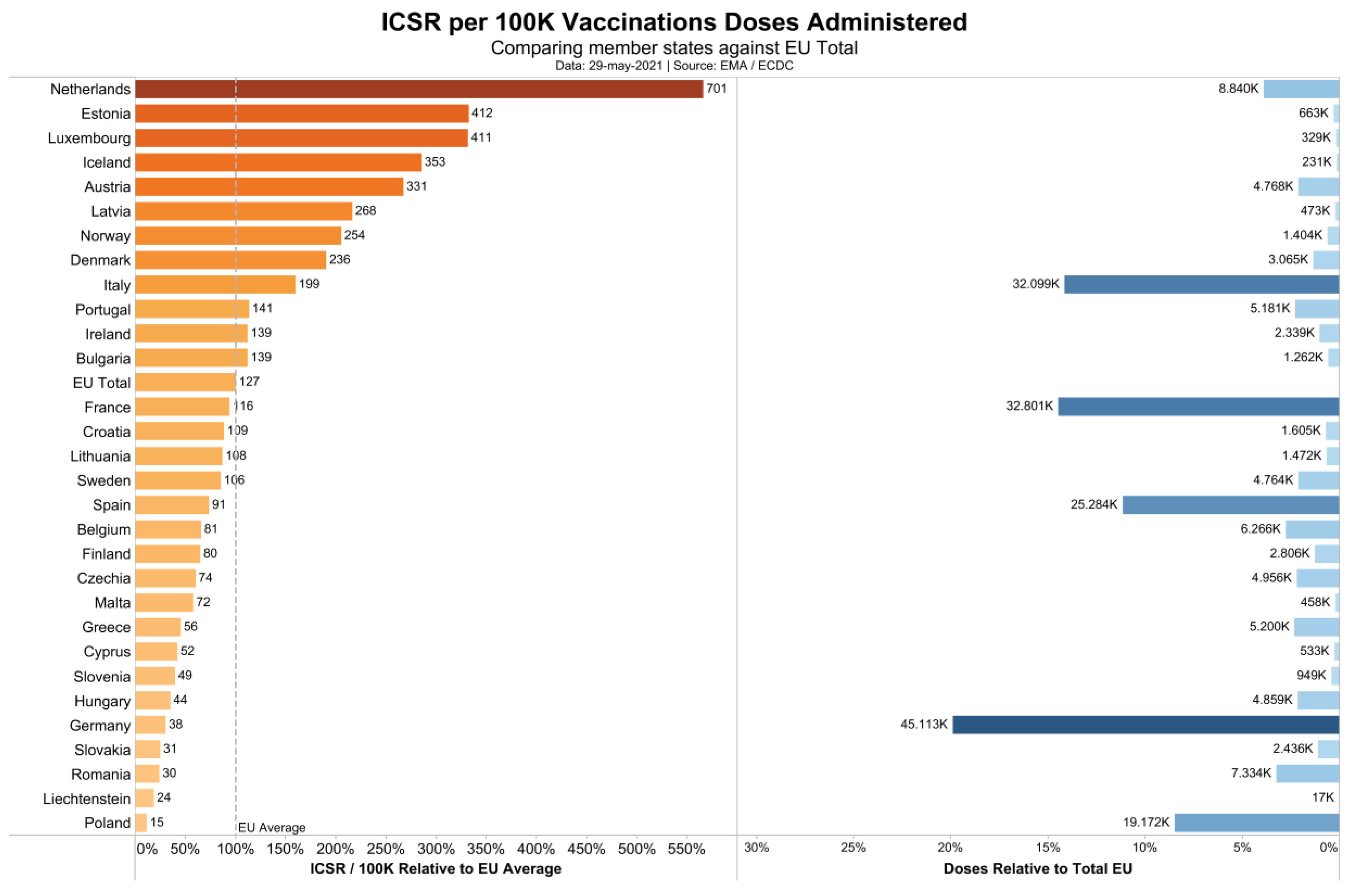

that the reporting of side effects varies by a factor of 47 (Figure 1).

While the European average is 127 individual case safety reports

(ICSRs), i.e., cases with side effect reports, per 100,000 vaccinations,

the Dutch authorities have registered 701 reports per 100,000

vaccinations, while Poland has registered only 15 ISCRs per 100,000

vaccinations. Assuming that this difference is not due to differential

national susceptibility to vaccination side effects, but due to

different national reporting standards, we decided to use the data of

the Dutch national register (https://www.lareb.nl/coronameldingen;

accessed on 29 May 2021) to gauge the number of severe and fatal side

effects per 100,000 vaccinations. We compare these quantities to the

NNTV to prevent one clinical case of and one fatality by COVID-19.

Figure 1.

Individual safety case reports in association with COVID 19 vaccines in Europe.

3. Results

Cunningham was the first

to point out the high NNTV in a non-peer-reviewed comment: Around 256

persons needed to vaccinate with the Pfizer vaccine to prevent one case [8]. A recent large field study in Israel with more than a million participants [6],

where Comirnaty, the mRNA vaccination product marketed by Pfizer, was

applied allowed us to calculate the figure more precisely. Table 1

presents the data of this study based on matched pairs, using

propensity score matching with a large number of baseline variables, in

which both the vaccinated and unvaccinated persons were still at risk at

the beginning of a specified period [6]. We mainly used the estimates from Table 1,

because they are likely closer to real life and derived from the

largest field study to date. However, we also report the data from the

phase 3 trials conducted for obtaining regulatory approval in Table 2 and used them for a sensitivity analysis.

Table 1.

Risk differences and number needed to vaccinate (NNTV) to prevent one

infection, one case of symptomatic illness, and one death from COVID-19.

Data from Dagan et al. [6], N = 596,618 in each group.

| | Documented Infection | Symptomatic Illness | Death from COVID-19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Risk Difference (No./1000 Persons) (95% CI) | NNTV (95% CI) | Risk Difference (No./1000 Persons) (95% CI) | NNTV (95% CI) | Risk Difference (No./1000 Persons) (95% CI) | NNTV (95% CI) |

| 14–20 days after first dose | 2.06 (1.70–2.40) | 486 (417–589) | 1.54 (1.28–1.80) | 650 (556–782) | 0.03 (0.01–0.07) | 33,334 (14,286–100,000) |

| 21–27 days after first dose | 2.31 (1.96–2.69) | 433 (372–511) | 1.34 (1.09–1.62) | 747 (618–918) | 0.06 (0.02–0.11) | 16,667 (9091–50,000) |

| 7 days after second dose to end of follow-up | 8.58 (6.22–11.18) | 117 (90–161) | 4.61 (3.29–6.53) | 217 (154–304) | NA | NA |

Data taken from Table 2 in Dagan et al.’s work. NNTV = 1/risk difference.

Table 2.

Number needed to vaccinate (NNTV) calculated from pivotal phase 3

regulatory trials of the SARS-CoV2 mRNA vaccines of Moderna,

BioNTech/Pfizer, and Sputnik (the vector vaccine of Astra-Zeneca is not

contained here, as the study [9] was active-controlled and not placebo-controlled).

| Vaccine | N Participants Vaccine Group | N Participants Placebo Group | CoV2 Positive End of Trial Vaccine Group | CoV2 Positive End of Trial Placebo Group | Absolute Risk Difference (ARD) | Number Needed to Vaccinate 1/ARR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderna [5] $ | 15,181(14,550 *) | 15,170 (14,598 *) | 19 (0.13%) 1 | 269 (1.77%) 1 | 0.0165 | 61 |

| Comirnaty (BioNTech/Pfizer) [4] $ | 18,860 | 18,846 | 8 (0.042%) 2 | 162 (0.86%) 2 | 0.00817 | 123 |

| Sputnik V [7] § | 14,964 | 4902 | 13 (0.087%) **,3 | 47 (1%) **,3 | 0.0091 | 110 |

*

Modified intention to treat-population—basis for calculation; ** taken

from the publication because of slightly different case numbers; $ outcome was a symptomatic COVID-19 case; § outcome was a confirmed infection by PCR-test; 1 after 6 weeks; 2 after 4 weeks; 3 after 3 weeks.

It should be noted that in the Israeli field study, the

cumulative incidence of the infection, visible in the control group

after seven days, was low (Kaplan–Meier estimate <0.5%; Figure 2 in

Dagan et al.’s work [6])

and remained below 3% after six weeks. In the other studies, the

incidence figures after three to six weeks in the placebo groups were

similarly low, between 0.85% and 1.8%. The absolute infection risk

reductions given by Dagan et al. [6]

translated into an NNTV of 486 (95% CI, 417–589) two to three weeks

after the first dose, or 117 (90–161) after the second dose until the

end of follow-up to prevent one documented case (Table 1). Estimates of NNTV to prevent CoV2 infection from the phase 3 trials of the most widely used vaccination products [3,4,5] were between 61 (Moderna) and 123 (Table 2) and were estimated to be 256 by Cunningham [8]. However, it should also be noted that the outcome “Documented infection” in Table 1 refers to CoV2 infection as defined by a positive PCR test, i.e., without considering false-positive results [10],

so that the outcome “symptomatic illness” may better reflect vaccine

effectiveness. If clinically symptomatic COVID-19 until the end of

follow-up was used as an outcome, the NNTV was estimated as 217 (95% CI,

154–304).

In the Israeli field study, 4460 persons in the

vaccination group became infected during the study period and nine

persons died, translating into an infection fatality rate (IFR) of 0.2%

in the vaccination group. In the control group, 6100 became infected and

32 died, resulting in an IFR of 0.5%, which is within the range found

by a review [11].

Using the data from Table 1,

we calculated the absolute risk difference to be 0.00006 (ARD for

preventing one death after three to four weeks), which translates into

an NNTV of 16,667. The 95% confidence interval spanned the range from

9000 to 50,000. Thus, between 9000 and 50,000 people need to be

vaccinated, with a point-estimate of roughly 16,000, to prevent one

COVID-19-related death.

For the other studies listed in Table 2, in the case that positive infection was the outcome [7],

we calculated the NNTV to prevent one death using the IFR estimate of

0.5%; in the case that clinically positive COVID-19 was the outcome [4,5],

we used the case fatality rate estimated as the number of worldwide

COVID-19 cases divided by COVID-19 related deaths, which was 2% (https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

(accessed on 29 May 2021)). In the case of the Sputnik vaccine, one

would thus have to vaccinate 22,000 people to prevent one death. In the

case of the Moderna vaccine, one would have to vaccinate 3050 people to

prevent one death. In the case of Comirnaty, the Pfizer vaccine, 6150

vaccinated people would prevent one death, although using the figure by

Cunningham [8], it would be 12,300 vaccinations to prevent one death.

The side effects data reported in the Dutch register (www.lareb.nl/coronameldingen (accessed on 27 May 2021)) are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Individual case safety reports for the most widely distributed COVID-19 vaccines according to the Dutch side effects register (www.lareb.nl/coronameldingen (accessed on 29 May 2021)), the absolute numbers per vaccine, and standardization per 100,000 vaccinations.

| General Number of Reports (1) | Serious Side Effects (1) | Deaths (2) | Number of Vaccinations According to (3) | Number of Vaccinations According to ECDC (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comirnaty (Pfizer) | 21,321 | 864 | 280 | 5,946,031 | 6,004,808 |

| Moderna | 6390 | 114 | 35 | 531,449 | 540,862 |

| Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) | 29,865 | 411 | 31 | 1,837,407 | 1,852,996 |

| Janssen | 2596 | 7 | - | 142,069 | 143,525 |

| Unknown | 129 | 15 | 5 | - | 540 |

| Total | 60,301 | 1.411 | 351 | 8,456,956 | 8,542,731 |

| Per 100,000 vaccinations according to Dutch data | 713.03 | 16.68 | 4.15 | | |

| Per 100,000 vaccinations according to ECDC | 705.87 | 16.52 | 4.11 | | |

(1) https://www.lareb.nl/coronameldingen. (2) https://www.lareb.nl/pages/update-van-bijwerkingen. (3) https://coronadashboard.rijksoverheid.nl/landelijk/vaccinaties. (4) https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/data-covid-19-vaccination-eu-eea. All sites accessed on 27 May 2021. The Dutch government reported two numbers; we took the calculated amounts.

Thus, we need to accept that around 16 cases will develop

severe adverse reactions from COVID-19 vaccines per 100,000 vaccinations

delivered, and approximately four people will die from the consequences

of being vaccinated per 100,000 vaccinations delivered. Adopting the

point estimate of NNTV = 16,000 (95% CI, 9000–50,000) to prevent one

COVID-19-related death, for every six (95% CI, 2–11) deaths prevented by

vaccination, we may incur four deaths as a consequence of or associated

with the vaccination. Simply put: As we prevent three deaths by

vaccinating, we incur two deaths.

The risk–benefit ratio looks

better if we accept the stronger effect sizes from the phase 3 trials.

Using Cunningham’s estimate of NNTV = 12,300, which stems from a

non-peer reviewed comment, we arrived at eight deaths prevented per

100,000 vaccinations and, in the best case, 33 deaths prevented by

100,000 vaccinations. Thus, in the optimum case, we risk four deaths to

prevent 33 deaths, a risk–benefit ratio of 1:8. The risk–benefit ratio

in terms of deaths prevented and deaths incurred thus ranges from 2:3 to

1:8, although real-life data also support ratios as high as 2:1, i.e.,

twice as high a risk of death from the vaccination compared to COVID-19,

within the 95% confidence limit.

4. Discussion

The

COVID-19 vaccines are immunologically effective and can—according to

the publications—prevent infections, morbidity, and mortality associated

with SARS-CoV2; however, they incur costs. Apart from the economic

costs, there are comparatively high rates of side effects and

fatalities. The current figure is around four fatalities per 100,000

vaccinations, as documented by the most thorough European documentation

system, the Dutch side effects register (lareb.nl). This tallies well

with a recently conducted analysis of the U.S. vaccine adverse reactions

reporting system, which found 3.4 fatalities per 100,000 vaccinations,

mostly with the Comirnaty (Pfizer) and Moderna vaccines [12].

Is

this a few or many? This is difficult to say, and the answer is

dependent on one’s view of how severe the pandemic is and whether the

common assumption that there is hardly any innate immunological defense

or cross-reactional immunity is true. Some argue that we can assume

cross-reactivity of antibodies to conventional coronaviruses in 30–50%

of the population [13,14,15,16]. This might explain why children and younger people are rarely afflicted by SARS-CoV2 [17,18,19]. An innate immune reaction is difficult to gauge. Thus, low seroprevalence figures [20,21,22]

may not only reflect a lack of herd immunity, but also a mix of

undetected cross-reactivity of antibodies to other coronaviruses, as

well as clearing of infection by innate immunity.

However, one

should consider the simple legal fact that a death associated with a

vaccination is different in kind and legal status from a death suffered

as a consequence of an incidental infection.

Our data should be viewed in the light of its inherent limitations:

The

study which we used to gauge the NNTV was a single field study, even

though it is the largest to date. The other data stem from regulatory

trials that were not designed to detect maximum effects. The field study

was somewhat specific to the situation in Israel, and studies in other

countries and other populations or other post-marketing surveillance

studies might reveal more beneficial clinical effect sizes when the

prevalence of the infection is higher. This field study also suffered

from some problems, as a lot of cases were censored due to unknown

reasons, presumably due to a loss to follow-up. However, the regulatory

studies compensate for some of the weaknesses, and thereby generate a

somewhat more beneficial risk–benefit ratio.

The ADR database of the EMA collects reports of different kinds, by doctors, patients, and authorities. We observed (Figure 1)

that the reporting standards vary hugely across countries. It might be

necessary for the EMA and for national governments to install better

monitoring procedures in order to generate more reliable data. Some

countries have tight reporting schemes, some report in a rather loose

fashion. As we have to assume that the average number of side effects is

roughly similar across countries, we would expect a similar reporting

quota. However, when inspecting the reports according to countries, we

can see a large variance. Our decision to use the Dutch data as a proxy

for Europe was derived from this discovery. One might want to challenge

this decision, but we did not find any data from other countries being

more valid than those used here. Apart from this, our data tallied well

with the data from the U.S. CDC vaccine adverse reporting system [12], which indirectly validates our decision.

One

might argue that it is always difficult to ascertain causality in such

reports. This is certainly true; however, the Dutch data, especially the

fatal cases, were certified by medical specialists (https://www.lareb.nl/media/eacjg2eq/beleidsplan-2015-2019.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2021)), page 13: “All

reports received are checked for completeness and possible ambiguities.

If necessary, additional information is requested from the reporting

party and/or the treating doctor The report is entered into the database

with all the necessary information. Side effects are coded according to

the applicable (international) standards. Subsequently an individual

assessment of the report is made. The reports are forwarded to the

European database (Eudravigilance) and the database of the WHO

Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring in Uppsala. The

registration holders are informed about the reports concerning their

product.”).

A recent experimental study showed that the SARS-CoV2 spike protein is sufficient to produce endothelial damage [23].

This provides a potential causal rationale for the most serious and

most frequent side effects, namely, vascular problems such as thrombotic

events. The vector-based COVID-19 vaccines can produce soluble spike

proteins, which multiply the potential damage sites [24].

The spike protein also contains domains that may bind to cholinergic

receptors, thereby compromising the cholinergic anti-inflammatory

pathways, enhancing inflammatory processes [25].

A recent review listed several other potential side effects of COVID-19

mRNA vaccines that may also emerge later than in the observation

periods covered here [26].

In

the Israeli field study, the observation period was six weeks, and in

the U.S. regulatory studies between four to six weeks, a period commonly

assumed to be sufficient to see a clinical effect of a vaccine, because

it would also be the time frame within which someone who was infected

initially would fall ill and perhaps die. Had the observation period

been longer, the clinical effect size might have increased, i.e., the

NNTV could have become lower and, consequently, the ratio of benefit to

harm could have increased in favor of the vaccines. However, as noted

above, there is also the possibility of side effects developing with

some delay and influencing the risk–benefit ratio in the opposite

direction [26]. This should be studied more systematically in a long-term observational study.

Another

point to consider is that initially, mainly older persons and those at

risk were entered into the national vaccination programs. It is to be

hoped that the tally of fatalities will become lower as a consequence of

the vaccinations, as the age of those vaccinated decreases.

However,

we do think that, given the data, we should not wait to see whether

more fatalities accrue, but instead use the data available to study who

might be at risk of suffering side effects and pursue a diligent route.

Finally,

we note that from experience with reporting side effects from other

drugs, only a small fraction of side effects is reported to adverse

events databases [27,28]. The median underreporting can be as high as 95% [29].

Given

this fact and the high number of serious side effects already reported,

the current political trend to vaccinate children who are at very low

risk of suffering from COVID-19 in the first place must be reconsidered.

5. Conclusions

The

present assessment raises the question whether it would be necessary to

rethink policies and use COVID-19 vaccines more sparingly and with some

discretion only in those that are willing to accept the risk because

they feel more at risk from the true infection than the mock infection.

Perhaps it might be necessary to dampen the enthusiasm by sober facts?

In our view, the EMA and national authorities should instigate a safety

review into the safety database of COVID-19 vaccines and governments

should carefully consider their policies in light of these data.

Ideally, independent scientists should carry out thorough case reviews

of the very severe cases, so that there can be evidence-based

recommendations on who is likely to benefit from a SARS-CoV2 vaccination

and who is in danger of suffering from side effects. Currently, our

estimates show that we have to accept four fatal and 16 serious side

effects per 100,000 vaccinations in order to save the lives of 2–11

individuals per 100,000 vaccinations, placing risks and benefits on the

same order of magnitude.